After watching the Hobbit movies (which I knew were going to be bad, but still managed to disapoint me) I went back to reading the book. As a kid I loved reading it, especially the chapter 'riddles in the dark', but I never considered it from an RPG perspective before. During my last readthrough I noticed a lot of things I liked and that I think could work in RPGs as well, so here are some ideas pillaged from the Hobbit I will keep in mind in the future:

1. Use a resolution system that allows for weird results

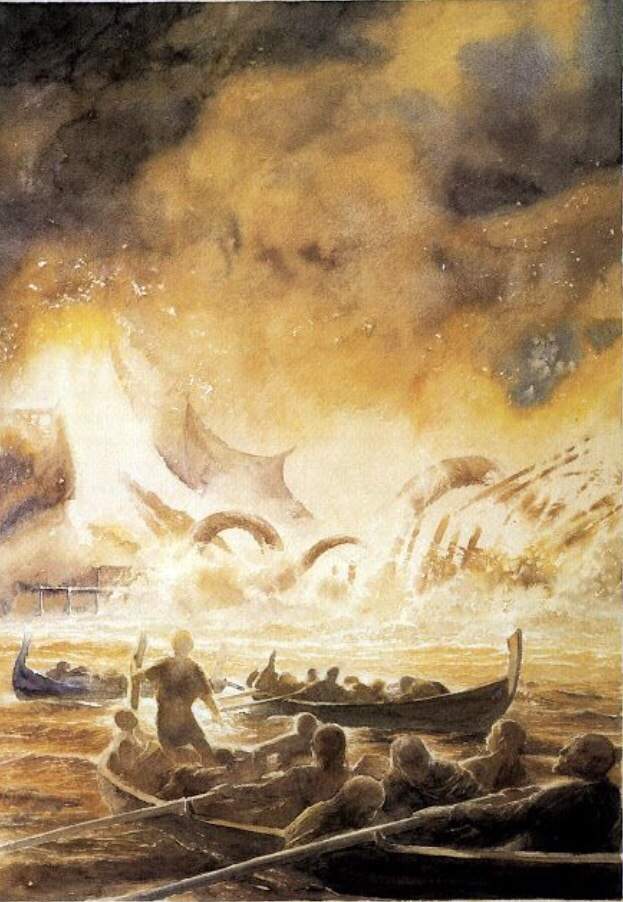

I like the way Smaug dies. This might be contentious, I've seen a lot of people critique how Smaug is killed by a random character that wasn't introduced earlier, but I like how it is unexpected and creates an entirely new problem. It also establishes the Men of the Lake as a faction with interests in the region (something Tolkien does well in general).

It might be saying more about me than it does about the resolution systems I use, but I don't think this would ever occur at my table, eventhough I think it is fantastic. If I ruled this in a common sense way, I would say 'the dragon clearly outmatches the tiny army of the Men of the Lake, so the town is destroyed but Smaug is away for a while.'

Really it is an argument for critical failure (or succes, depending on if you rolled for Smaug or for Bard), or some other way to generate incredibly unlikely results that surprise both the players and the GM, shifting the entire situation for better or worse.

2. Focus on 'adventures' as oppposed to the 'Adventure'

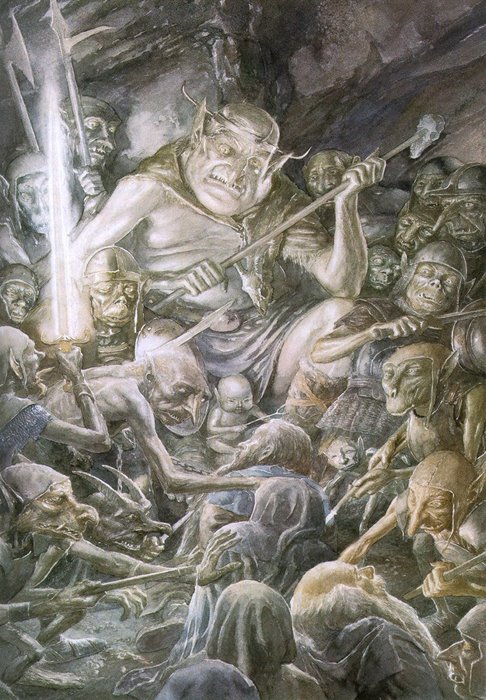

The Hobbit is structured like a collection of bedtime stories: every chapter contains a nice little adventure from the perspective of the Hobbit: Dwarves ask you to go on an adventure, Trolls try to eat you, you visit the Elves, get captured by Goblins, play a riddle game with Gollum, etc.

Clearly there is the Adventure: take back the Treasure from the Dragon, but the smaller adventures get the focus throughout the book. Even getting over the Misty Mountains or making it through Mirkwood gets broken up into multiple smaller adventures.

I play very irregularly, and I have the most success with my players when we have smaller stories that begin and end in the same session. Trying to make every session into an adventure in its own right by breaking up the larger adventure is something I want to try aiming for more.

It is also funny to me how the Hobbit book has far less emphasis on the larger Adventure than the movies, yet the book is far better at making the actions of the characters feel impactful: The goblins don't attack the lonely mountain because of something that happened in the past before the adventure began (like they do in the movies), they attack the mountain in part as revenge for the Dwarves killing the Great Goblin.

3. Communicate the goals and relations of factions

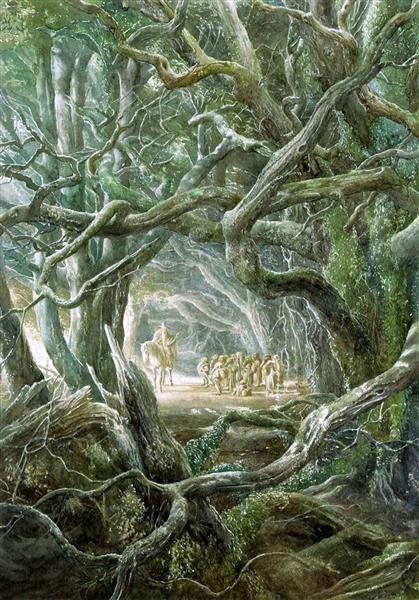

This might just be me, but I don't mind the Eagles as much as a cop out. At least, I don't mind them in the book, in the movies they annoy me like crazy. The difference is how the Eagles are protrayed: we are given nothing other than that the Eagles are big in the movies, so they seem like a lazy excuse to get our heroes out of a pickle. In the book the Eagles talk, patrol their lands, have a King, oppose the goblins, etc.

The same is true for the Wargs the party encounters when exiting the Misty Mountains. This is not just an encounter with wolves, it is a raiding party waiting for goblins to go mess stuff up. What could have been a boring encounter with wolves (or just another fight with the same boring ass orcs that have been chasing the characters for some reason from the start), turns into an opportunity to teach us something about the world: Wolves hang with Goblins and they raid the human villages in the area.

Giving a group goals and ideals is basic worldbuilding 101. However, the Eagles might have had the same organization and political relations in the movies as they had in the book and the wolves might not just be mounts but an ally to the orcs. But if I don't know it doesn't matter and the same is true for players. Your factions are empty and cheap if you don't communicate their goals and relations.

4. Things are more fun if they talk

Giant spiders are good. Talking giant spiders that you can piss off by insulting them is better. Wolves that scheme are fun, overhearing their discussion because you happen to speak their language is awesome. Using a bird to carry a message is cool, but having crows talk shit about you, willfully ignoring the counsel of ravens and having them bring messages orally is freaking awesome.

It also makes point 3 a lot easier to accomplish. If you can overhear the Eagles discus how much they hate the Goblins or the Wargs argue they best wait for reinforcements from the Goblins you have just communicated relations.

I've made an enitre post about why I like it when you can talk to stuff, so if you want to hear my reasoning just read that.

5. Make people generally nice

The elves at the house of Elrond are just straight up nice. They aren't cold or regal, but merry and singing and having fun and just actually really nice. And it was so weird to read that, because it is missing from a lot fantasy which is a shame.

Not only do I think it is good to make nice more of a normal thing, it also contrasts the missery of being on the road without food, or being webbed by spiders. If every town is misserable, if every person is secretly out to get you or complex and brooding and serious, then what are we doing when we go on adventure? It is way easier to make faux medieval travel seem as shitty as it was if you raise the bar of what is 'normal' to 'everyone is nice and we are having a blast'.

Being nice also doesn't mean having nothing going on. Beorn is nice, but clearly has his own beliefs about how you should live (and dislikes people that do the exact opposite). Also he probably has something of an anger problem, which doesn't mean you can't be nice.

Moreover, people might be generally nice, but change their opinion of you if they find themselves in a bad situation or if you wronged them in their eyes. The people of Lake Town are a great example of this.

Basically: nice isn't the same as boring, it is a nice contrast to the nastyness the world has to offer.

6. Weirdly specific weaknesses

One of the reasons the Hobbit feels like more of a fairy tale than the Lord of the Rings is the focus on weirdly specific weaknesses. You don't beat the trolls by fighting them (though you might be able to if you army is big enough), you get them to fight each other until daybreak. You don't kill the dragon with endless volleys of arrows, but with a well aimed shot at its weakspot.

Even when fighting animals, using fire because the wolves don't like it and having Goblins flee at the sight of legendary Goblin slaying swords makes the world seem so much more interesting then just having to fight them.

7. Obstacles can be assets

This is a tried and true statement within more dungeon based RPGs, but it was interesting to see this in a mostly dungeon free context. The Enchanted River in Mirkwood is a great OSR problem that I could see players attempting to use after they manage to overcome it, but Bilbo sneaking after Gollum to find the way out of the tunnels is another great example.

8. Make entrances meaningfully different

The jailbreak from the elven dungeons is a classic, but the reason it works so well is because there is a reason for the backdoor. Having multiple entrances itself isn't enough, making those entrances fulfill certain functions makes them more memorable and more actionable. Players could easily have come up with the barrel plan, but only because the second entrance isn't just another magic door like the main entrance. Different entrances allow for different approaches, especially if they have a high jinks potential.

9. Stuff can happen during denoument

Denoument, i.e. the release of tension at the end of a story, is traditionally a longer version of 'and they lived happily ever after'. The Hobbit doesn't end that way, instead of coming home and living happily ever after, all of Bilbo's stuff is sold and he has to go through pains to get everything back. Contrasting diplomatic efforts to stop a war and saving your friends from certain death with proving you are in fact not dead and getting all your stuff that was auctioned off back keeps the end of the story interactive, while there is still a clear change of what is at stake.

10. Give player outdated information

This last one is one that I am not quite sure of, but that I would definitely like to try. If all advice the dwarves got was sound they would never have to encounter significant difficulties. Tolkien goes hard on this: everytime the party chooses a road through a dangerous area, it turns out the information they got was outdated.

Now I am a big fan of Chris McDowall's ICI and would rather give players as much inforation that is accurate as possible. But having situations change over time makes the world seem alive and sets a certain tone for the world, which in Tolkien is a sense of things getting worse before they can finally become better towards the end of the book.

It is also a bit more realistic (which isn't super important, but can help with immersion): If everyone avoids the road know for having lots of robbers, the robbers will eventualy take their business elsewhere.

To conform with ICI, I would probably let my players know this information could be outdated if they ask about it. They might not do this the first time, but once they get screwed by bad information once, the players will learn to be more inquisitive about this stuff, which I will always reward with more information.

Appendix:

It was a lot of fun revisiting The Hobbit after all this time. There was a lot that I can appreciate now that I am older, but unfortunately there is also a lot of problematic stuff in there I didn't notice before.

I can sort of deal with the entire divine right of kings, as it is faux-medieval (though I do tire of that trope), but there is a lot of weird classism in the depiction of Trolls and Goblins that was a little bit painful. Also, I am very uncomfortable with the way dwarves are depicted, as it lends itself a little too well for an antisemetic reading (a people without a home, weird beards, long noses, obsessed with money).

Still, I can enjoy something without needing it to be perfect. Just a little irksome in the parts of the book where it features more heavily.

Hello. I loved your post, but I wanted to address the comment about antisemitism (I'm a Jew, for what it's worth). Tolkien was very much NOT antisemitic - we know this from his writings/letters but also most famously from his rejection of Nazi-era requirements to publish in Germany:

ReplyDeletehttps://www.openculture.com/2014/04/j-r-r-tolkien-snubs-a-german-publisher.html

"25 July 1938

20 Northmoor Road, Oxford

Dear Sirs,

Thank you for your letter. I regret that I am not clear as to what you intend by arisch. I am not of Aryan extraction: that is Indo-Iranian; as far as I am aware none of my ancestors spoke Hindustani, Persian, Gypsy, or any related dialects. But if I am to understand that you are enquiring whether I am of Jewish origin, I can only reply that I regret that I appear to have no ancestors of that gifted people. My great-great-grandfather came to England in the eighteenth century from Germany: the main part of my descent is therefore purely English, and I am an English subject — which should be sufficient. I have been accustomed, nonetheless, to regard my German name with pride, and continued to do so throughout the period of the late regrettable war, in which I served in the English army. I cannot, however, forbear to comment that if impertinent and irrelevant inquiries of this sort are to become the rule in matters of literature, then the time is not far distant when a German name will no longer be a source of pride.

Your enquiry is doubtless made in order to comply with the laws of your own country, but that this should be held to apply to the subjects of another state would be improper, even if it had (as it has not) any bearing whatsoever on the merits of my work or its sustainability for publication, of which you appear to have satisfied yourselves without reference to my Abstammung.

I trust you will find this reply satisfactory, and remain yours faithfully,

J. R. R. Tolkien"

I don't think Tolkien was a deliberate, malicious antisemite. However, he did admit the Dwarves are based on jews in a BBC radio interview and the things he says about them in the Hobbit are a little iffy imo.

DeleteBut even if he was completely well meaning and the dwarves were not directly based on the jews, I think that the depiction lends itself too easily for an antisemetic reading, i.e. someone could find validation for their explicit antisemetic beliefs by recognizing these stereotypical characteristics as 'jewish', assuming that Tolkien agrees with them.

It did not stop me from liking the book, but I just didn't see the need for making a race greedy if that race is already coded and inspired by a people group that is often falsely accused of greed.

I am very happy to read that he was against the explicit and horrific antisemitism going on in Germany at the time though!

Yes, the physical depiction was a fairly common trope used by antisemites, especially at the time.

DeleteInterestingly, I've seen depictions of Palestinian politicians today that look very similar as well. As an Israeli, this sort of irony is not lost on me.